I dug my toes into the sand of the Delaware beach, hugged my knees, and drew as close to the campfire as I could. The flames warmed our faces while behind us the night air chilled our backs. Huddled with my sisters and cousin, I smelled the burning logs and breathed in the fire’s heat. We all sat in awe of my father. He stood across the campfire from us, a figure a-swirl in rising heat and smoke, his face underlit by flame as if he were a prophet on Mount Sinai. We clutched each other as he wove his story.

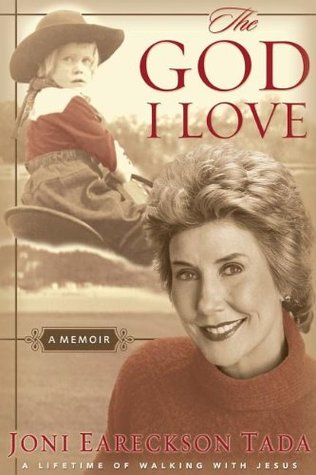

This isn't Joni Eareckson Tada's first autobiography. It differs from Joni in that it explores more of her life before and after the diving accident and paralysis. One gets a better picture of her childhood, her family, her hobbies and interests, the times in which she lived, her faith and culture. One also gets a better picture of her faith and ministry after the accident. (Though her accident was no accident, but a work of God's providence.) Joni was published in 1976. So much has happened SINCE the publication of that book. Her marriage, her ministry, her mission trips, her public fight for the rights of the disabled, just to name a few! So even if you've read Joni, you don't know the whole story.

The God I Love, I noticed is almost a love letter to her father and mother--a big thank you. But above all, the focus is on God himself.

Quotes:

My earliest recollections of being stirred by the Spirit happened through hymns. Five-year-olds are able to tuck words into cubbyholes in their hearts, like secret notes stored for a rainy day. All that mattered to me now was that these hymns bound me to the melody of my parents and sisters. The songs had something to do with God, my father, my family, and a small seed of faith safely stored in a heart-closet.

God was only a little bigger than my father. The Lord may have filled the universe, but my dad filled mine. Whereas God kept the planets orbiting, my father was the center of our orbit. And whatever he commanded us was spoken not so much with words but through the sheer force of his own good character. In the spring of 1961, it was God’s responsibility to show young President Kennedy how to run a country, to keep the Russians on their side of the earth, to bring Adolf Eichmann to trial, to keep the Bomb from falling on Woodlawn Elementary, and The Creature from the Black Lagoon in his swamp and out of our neighborhood. Everything else was Daddy’s responsibility.

To not believe God was up there was, well, impossible. For one thing, there were the Ten Commandments posted at the front of our classroom, right underneath the American flag. No day at Woodlawn Elementary — at least back in the fifties and early sixties — dared start without a series of rituals: a U.S. Saving Stamps pitch to keep our country strong; the Pledge of Allegiance, to assure liberty and justice for all; the collection of lunch money (thirty-five cents for grilled cheese sandwich, tomato soup, carton of milk, and a Nutty Buddy); all capped off by a daily reading from the Bible.

I wanted to be on God’s side. So I became one of a mass of young people who searched, as one poet put it, for God and truth and right. Some of my passion was fostered by class discussions on segregation. We were assigned to read a book called Black Like Me by John Howard Griffin, the true story of a white man who colored his skin black and journeyed south to experience firsthand the stigma of segregation. The hate and horror this man faced left a deep impression on me. My search for truth and right began heating up. I memorized the protest songs of Peter, Paul, and Mary, as well as Joan Baez. I paid attention as the pastor of the little United Methodist Church we attended up by the farm pounded his pulpit about racism and social inequalities. I hung on every word of Mr. Lee as he urged us to examine the issues that were ripping society apart. We discussed injustices in the classroom and brought to light things that needed changing. “Let justice roll down like the mighty waters!” went the Bible verse, quoted from pulpits and coffeehouse stages alike. Yes, God was in. And if I was going to be on God’s side, I had to get better connected with him.

My hair. It became one of two miracles everyone whispered about those first few days at the University of Maryland Hospital. My shocking blonde hair had floated on the surface as I lay half submerged in the water. The other miracle was the blue crab that bit Kathy’s toe just before she stepped out of the shallows and onto the beach. Any other time, Kathy would have bolted to escape what she was convinced were zillions of hungry crabs. But this time, she didn’t race to the safety of her towel. Instead, she turned to warn her little sister. Her sister, whose bright-yellow hair, ebbing and flowing, told her something was wrong.

Something was happening, something for the first time since Jacque lay next to me in the night, singing “Man of Sorrows”: I was caught up in God’s thoughts about me, not my thoughts about him. I was lying in a stream of sunshine, consumed by his compassion for me, not by my anger and doubt about him. My thoughts didn’t even matter now — only his did. Only his mind, his heart. And his mind and heart were communicating clearly, as clearly as all those visionary moments I rode the horse trail, brushing past tree limbs, as clearly as all those nights by the ocean, under the stars. And he was saying, “Come unto me. Let me give you rest.” Yes, yes, I whimpered in my thoughts, I need rest, I just want rest. Rest and peace. God was oh-so clever. During all the chaos in my life, he remained silent for a long, long time. And then — voilà! — he broke through with a quick-witted surprise, a keen twist, an unexpected but brilliant turn of events — like this statue. I would bang-bang-bang on heaven’s door, firing daggers and darts, trying to manipulate him. I would blacken a white page with ink. I’d wail and sulk and thrash my head on a pillow to break my neck higher for spite. And then, this. God would answer, quietly and dramatically. Lying there, I didn’t try to analyze it much more than that. I simply looked into Jesus’ face and basked in his blessing. I hadn’t expected anything like this when I was wheeled into Johns Hopkins. I was here to get my nails cut out. But now I was thinking about other nails, staring at the scars they’d left in the hands of God’s Son. His nails for mine. Here was a God who understood my suffering.

“I like your wheelchair, Aunt Joni,” Kelly told me softly one evening. The two of us were sitting alone at the dinner table, waiting for the others to join us. “You do?” “Yeah,” she said, giving me her endearing grin. “I want one like yours when I grow up.” She caught me up short. All I could do was smile and shake my head at those impish eyes and thick eyelashes, the mop of brown hair cropped from the surgery, the freckles that flattened over her nose and cheeks when she laughed. Kelly scrunched her shoulders and leaned forward in her wheelchair, repeating, “Can I have one like yours?” I gulped hard. In her eyes, my wheelchair was more to be desired than a new collection of My Little Pony dolls or a spiffy new tea set for her and Kay. My chair was a joyride, a passport to adventure. Kelly assumed that my wheels had initiated me into a very special club, a club in which she wanted membership. Yet she didn’t seem to have a clue about the price one actually pays to join such a club. She seemed to discount the pain and the paralysis, the disappointment and the broken dreams. She utterly disregarded the dark side — it wasn’t even worth considering. All she longed for was a chance to be like me, to identify with me, to know Aunt Joni better. But something else was going on too. Those wise eyes of hers gave it away. Kelly wanted me to desire my wheelchair as much as she did. My niece wasn’t just admiring it — she wanted me to do the same. All along I had been trying to cheer her up, to tell her stories and play games with her, even be an example to her. But I had it all wrong. She was leading me. Out of the mouth of this babe, God was showing me how to embrace his will. “Your wheelchair’s neater than mine. I like yours best,” she said again. And you should too, she was saying. Kelly knew — at least, she sure seemed to know — that I was still bogged down by broken dreams. She sensed I still struggled with the dark side, that I didn’t quite know how to accept where I sat. For her, though, it was a cinch. Life had been hard on the farm, her parents argued a lot, and up until the diagnosis of cancer, you couldn’t get her near a tea set. But her suffering had pushed her into the arms of Jesus, and her gracious, openhearted way of accepting — no, embracing — his will had cracked open heaven’s floodgates of blessing. All my niece wanted to do now was talk about Jesus and his heaven, where she would pet giraffes and eat all the ice cream she wanted. Where she would ride bigger ponies, douse ketchup on everything, converse with Papa and Mama Bear, play with Baby Bear, and become an instant grownup.

“Think of a greater affliction — his affliction,” he added. “As you do, you can’t help but embrace him. And as you embrace him, you can’t help but love his will.” That meant something. It was being sure of something I hoped for — being certain of something I couldn’t see. It was, I realized, what having greater faith meant. Not faith in my ability to accept a wheelchair, but faith to embrace Christ, to trust him in spite of — no, because of — my problems. Again, I recalled the first time I tasted the power of the gospel that night in the hills of Virginia. How could I doubt the one who gave his life up for me? I remembered my friend Jacque singing to me in the hospital, the statue at Johns Hopkins, my pleasant life with Jay on the farm, Kelly — and, as always, the stars above the campfires. They were all part of the path Jesus had led me on thus far. How could I not believe him?

“Just make sure you keep pointing people to the Bible,” he finally offered. “Your life story can’t change anyone, but God’s Word can.”

The weaker we are, the harder we must lean on God — and the harder we lean on him, the stronger we discover him to be.

The truly handicapped among us are those who start their mornings on automatic cruise control, without needing God. But he gives strength to all who cry to him for help. So, who are the weak and needy? Who are those who need his help?” A brief pause in the dark shadow of recent events always allowed the point to come home. “It’s you. It’s me.”

© Becky Laney of Operation Actually Read Bible

No comments:

Post a Comment