First sentence: If sales are signs, then C.S. Lewis is one of the most popular Christian theologians being published in the United States today.

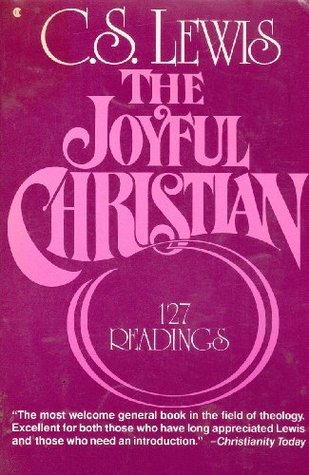

The Joyful Christian is a collection of 127 readings taken from C.S. Lewis' nonfiction works. Some readings are longer than others--a few pages in length. Other readings are much shorter--less than a single page. Some readings seem to flow together in a particular sequence. Others not as much. Either is fine as far as I'm concerned when it comes to devotional readings.

I think there is a definite place for devotional books that are not 365 days! It can be a little overwhelming to "commit" to reading a particular devotional book for an entire year. There's also something about a book being dated--literally. The dates can mock you if you fail.

- To some, God is discoverable everywhere; to others, nowhere. Those who do not find Him on earth are unlikely to find Him in space. But send a saint up in a spaceship and he'll find God in space as he found God on earth. Much depends on the seeing eye. (6)

- If God is Love, He is by definition, more than mere kindness. And it appears, from all records, that though He has often rebuked us and condemned us, He has never regarded us with contempt. He has paid us the intolerable compliment of loving us, in the deepest, most tragic, most inexorable sense. (39)

- The Son of God became a man to enable men to become sons of God. (50)

- The doctrine of the Second Coming teaches us that we do not and cannot know when the world drama will end. The curtain may be rung down at any moment...We do not know the play. We do not even know whether we are in Act I or Act V. We do not know who are the major and the minor characters. The Author knows. The audience, if there is an audience (if angels and archangels and all the company of Heaven fill the pit ant the stalls), may have an inkling. But we, never seeing the play from outside, never meeting any characters except the tiny minority who are "on" in the same scenes as ourselves, wholly ignorant of the future and very imperfectly informed about the past, cannot tell at what moment the end ought to come. That it will come when it ought, we may be sure; but we waste our time in guessing when that will be. That it has meaning we may be sure, but we cannot see it. When it is over, we may be told. We are led to expect that the Author will have something to say to each of us on the part that each of us has played. The playing it well is what matters infinitely. (71)

- There is really some excuse for the man who said, "I wish they'd remember that the charge to Peter was Feed my sheep; not Try experiments on my rats, or even Teach my performing dogs new tricks." (81)

- For me words are...secondary. They are only an anchor. Or, shall I say, they are the movements of a conductor's baton: not the music. (85)

- We are always, completely and therefore equally, known to God. That is our destiny whether we like it or not. But though this knowledge never varies, the quality of our being known can. (90)

- It is a good rule, after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between. If that is too much for you, you should at least read one old one to every three new ones. (103)

- I think we delight to praise what we enjoy because the praise not merely expresses but completes the enjoyment; it is its appointed consummation. (119)

- In commanding us to glorify Him, God is inviting us to enjoy Him. (120)

- And finally--though it may seem a sour paradox--we must sometimes get away from the Authorized Version if for no other reason, simply because it is so beautiful and so solemn. Beauty exalts; but beauty also lulls. (123)

- If anyone would like to acquire humility, I can, I think, tell him the first step. The first step is to realize that one is proud. And a biggish step, too. At least, nothing whatever can be done before it. If you think you are not conceited, it means you are very conceited indeed. (141)

- I remember Christian teachers telling me long ago that I must hate a bad man's actions, but not hate the bad man: or, as they would say, hate the sin but not the sinner. For a long time I used think this a silly, straw-splitting distinction: how could you hate what a man did and not hate the man? But years later it occurred to me that there was one man to whom I had been doing this all my life--namely myself. However much I might dislike my own cowardice or conceit or greed, I went on loving myself. There had never been the slightest difficulty about it. In fact, the very reason why I hated the things was that I loved the man. Just because I loved myself, I was sorry to find that I was the sort of man who did those things. Consequently Christianity does not want us to reduce by one atom the hatred we feel for cruelty and treachery. We ought to hate them. Not one word of what we have said about them needs to be unsaid. But it does want us to hate them in the same way in which we hate things in ourselves: being sorry that the man should have done such things, and hoping, if it is anyway possible, that somehow, sometime, somewhere, he can be cured and made human again. (143)

- Christ takes it for granted that men are bad. Until we really feel this assumption of His to be true, though we are part of the world He came to save, we are not part of the audience to whom His words are addressed. (167)

© Becky Laney of Operation Actually Read Bible

No comments:

Post a Comment