First sentence: The Rev. Septimus Harding was, a few years since, a beneficed clergyman residing in the cathedral town of ––––; let us call it Barchester.

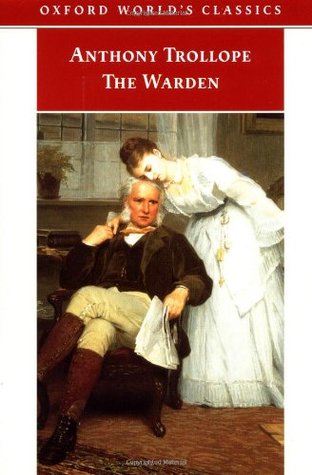

I make no secret of the fact that I LOVE, LOVE, LOVE Anthony Trollope. The Warden is the first in his Barchester series. And, I believe, it was the first Trollope novel I read. I first read and reviewed it in the spring of 2009.

I loved rereading it. I loved going back and visiting with these characters particularly the character of Mr. Harding. As much as I enjoy the other characters, I LOVE, LOVE, LOVE Mr. Harding. He's such a dear old soul.

Reasons you should read The Warden

- As one of Trollope's shorter novels, it's a great introduction to his work.

- It is the first book in a series, his Barchester series, which is FANTASTIC.

- It is all about the characters and relationships between characters. Sure, there's a plot, but, it's not an action-packed plot. It's all about ethics. Is it right or is it wrong for Mr. Harding to receive the salary he does?!

- The writing is delightful.

It's about one man, Mr. Harding, and his family: two daughters, one married, the other quite single. It's also about Harding's neighborhood and circle of friends. It's about the necessity of having a good reputation and a clean conscience.

Eleanor is the apple of her daddy's eye. Susan is married to an Archdeacon (Grantley). Because of his eldest daughters good fortune in marriage, Mr. Harding, has been named warden of Hiram's Hospital (alms house). The 'enemy' of Mr. Harding (and the suitor of Eleanor) is a young man named John Bold. When we are first introduced to these characters, we are learning that Bold is encouraging a law suit against Mr. Harding. He feels that Mr. Harding is in violation of the will. (Way, way, way back when (several centuries past), a man left his (quite wealthy) estate to the church. The church followed the will for the most part, but as times changed, they changed the way they carried it out. They were following it through in spirit in a way: still seeking to take care of twelve poor men (bedesman) but over time the salary of the warden increased.) Bold has stirred up the twelve bedesmen into signing a petition demanding justice, demanding more money, demanding 'fairer' distribution of funds.

The book presents this case through multiple perspectives: through two Grantleys (father and son), a few lawyers, Mr. Harding and Mr. Bold, of course, and through a handful of the twelve men involved that would profit from the change. There is one man whose voice seems louder than all the rest. And that voice comes from the newspaper, the Jupiter, one journalist writes harsh, condemning words directed at Mr. Harding--he assumes much having never met Harding personally. These words weigh heavy on the heart and soul of Mr. Harding. (And they don't sit easy on Mr. Bold either.)

Can Mr. Harding get his reputation back? What is the right thing to do? Is he in violation of the will? Is the church? What is his moral responsibility in caring for these twelve poor-and-retired men? What is his responsibility to the community?

Favorite quotes:

- Did ye ever know a poor man yet was the better for law, or for a lawyer?

- They say that faint heart never won fair lady; and it is amazing to me how fair ladies are won, so faint are often men’s hearts!

- “Why, my lord, there are two ways of giving advice: there is advice that may be good for the present day; and there is advice that may be good for days to come: now I cannot bring myself to give the former, if it be incompatible with the other.”

- ‘Everyone knows where his own shoe pinches!’

- Velvet and gilding do not make a throne, nor gold and jewels a sceptre. It is a throne because the most exalted one sits there, — and a sceptre because the most mighty one wields it.

- No established religion has ever been without its unbelievers, even in the country where it is the most firmly fixed; no creed has been without scoffers; no church has so prospered as to free itself entirely from dissent.

- “Nobody and everybody are always very kind, but unfortunately are generally very wrong.”

- Certain men are employed in writing for the public press; and if they are induced either to write or to abstain from writing by private motives, surely the public press would soon be of little value.

- “The public is defrauded,” said he, “whenever private considerations are allowed to have weight.”

- The public is defrauded when it is purposely misled. Poor public! how often is it misled! against what a world of fraud has it to contend!

- What is any newspaper article but an expression of the views taken by one side? Truth! it takes an age to ascertain the truth of any question!

- Ridicule is found to be more convincing than argument, imaginary agonies touch more than true sorrows, and monthly novels convince, when learned quartos fail to do so. If the world is to be set right, the work will be done by shilling numbers.

- It appears to us a question whether any clergyman can go through our church service with decorum, morning after morning, in an immense building, surrounded by not more than a dozen listeners. The best actors cannot act well before empty benches, and though there is, of course, a higher motive in one case than the other, still even the best of clergymen cannot but be influenced by their audience; and to expect that a duty should be well done under such circumstances, would be to require from human nature more than human power.

- What on earth could be more luxurious than a sofa, a book, and a cup of coffee?

- A man is the best judge of what he feels himself.

- “I have done more than sleep upon it,” said the warden; “I have lain awake upon it, and that night after night. I found I could not sleep upon it: now I hope to do so.”

- “It can never be rash to do right,” said he.

- We fear that he is represented in these pages as being worse than he is; but we have had to do with his foibles, and not with his virtues. We have seen only the weak side of the man, and have lacked the opportunity of bringing him forward on his strong ground. That he is a man somewhat too fond of his own way, and not sufficiently scrupulous in his manner of achieving it, his best friends cannot deny. That he is bigoted in favour, not so much of his doctrines as of his cloth, is also true: and it is true that the possession of a large income is a desire that sits near his heart.

© Becky Laney of Operation Actually Read Bible

No comments:

Post a Comment